Ski season is here, but while the eastern half of the U.S.digs out from wintery storms, the western U.S. snow season has been off to a very slow start.

The snowpack wasfar below normalacross most of the West on Dec. 1, 2025. Denver didn't see its first measurable snowfall until Nov. 29 – more than a month past normal, and one of itslatest first-snow dates on record.

But a late start isn't necessarily reason to worry about the snow season ahead.

Adrienne Marshall, ahydrologist in Coloradowho studies how snowfall is changing in the West, explains what forecasters are watching and how rising temperatures are affecting the future of the West's beloved snow.

What are snow forecasters paying attention to right now?

It's still early in the snow season, so there's a lot of uncertainty in the forecasts. A late first snow doesn't necessarily mean a low-snow year.

But there are some patterns that we know influence snowfall that forecasters are watching.

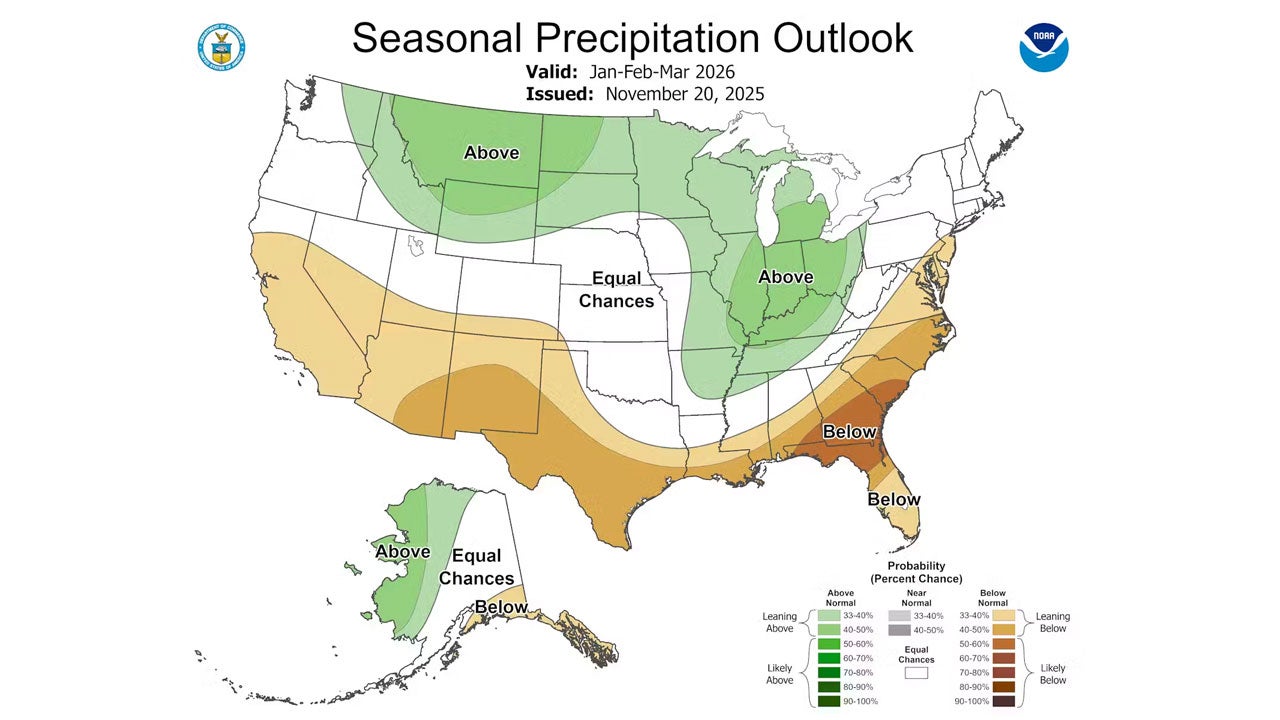

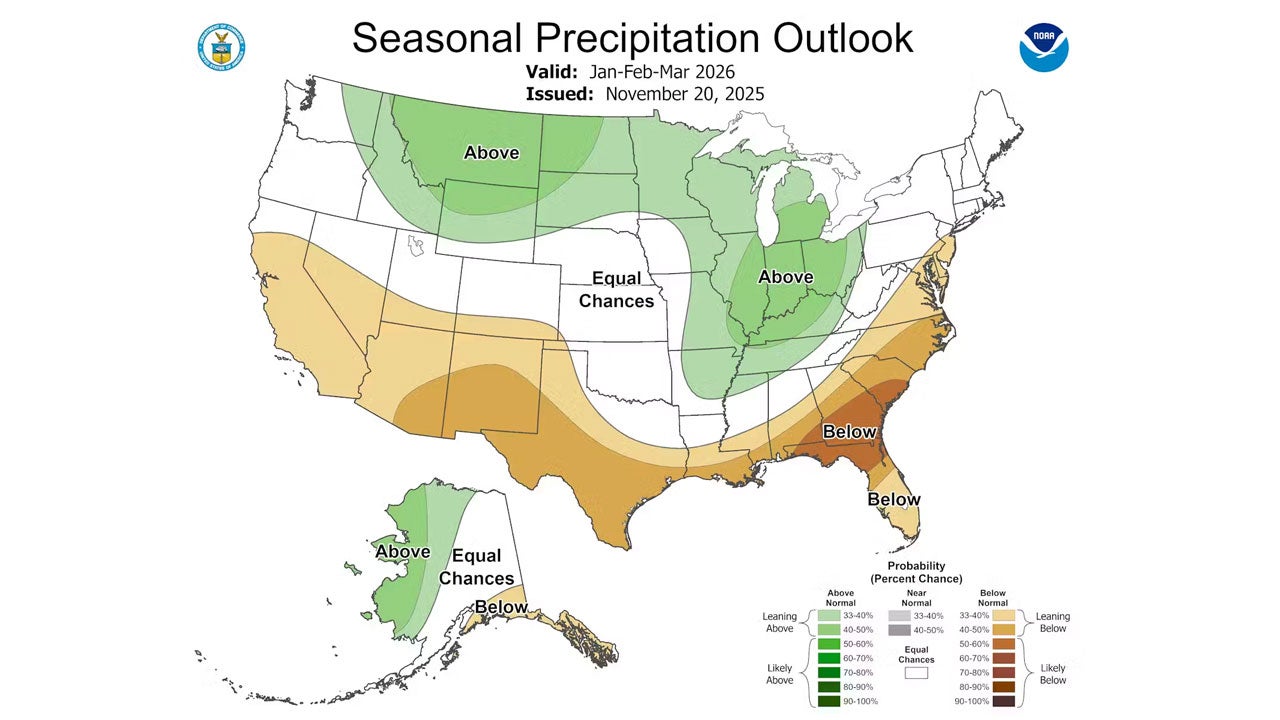

For example, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administrationis forecasting La Niña conditions for this winter, possibly switching to neutral midway through. La Niña involves cooler-than-usual sea-surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean along the equator west of South America. Cooler ocean temperatures in that regioncan influence weather patternsacross the U.S., but so can several other factors.

La Niña – and its opposite, El Niño – don't tell us what will happen for certain. Instead, they load the dice toward wetter or drier conditions, depending on where you are. La Niñas aregenerally associatedwith cooler, wetter conditions in the Pacific Northwest and a little bit warmer, drier conditions in the U.S. Southwest, but not always.

When we look at the consequences for snow, La Niña does tend to mean more snow in the Pacific Northwest and less in the Southwest, but, again, there's a lot of variability.

Snow conditions also depend heavily on individual storms, and those are more random than the seasonal pattern indicated by La Niña.

If you look atNOAA's seasonal outlook maps, most of Colorado and Utah are in the gap between the cooler and wetter pattern to the north and the warmer and drier pattern to the south expected during winter 2026. So, the outlook suggests roughly equal chances of more or less snow than normal and warmer or cooler weather across many major ski areas.

How is climate change affecting snowfall in the West?

In the West, snow measurements date back a century, so we can see some trends.

Starting in the 1920s, surveyors would go out into the mountains andmeasure the snowpackin March and April every year. Those records suggestsnowfall has declinedin most of the West. We also see evidence ofmore midwinter melting.

How much snow falls is driven by both temperature and precipitation, andtemperature is warming.

In the past few years, research has been able todirectly attribute observed changesin the spring snowpack to human-caused climate change. Rising temperatures have led to decreases in snow, particularly in the Southwest. The effects of warming temperatures on overall precipitation are less clear, but the net effect in the western U.S. is a decrease in the spring snowpack.

When we look atclimate change projections for the western U.S.in future years, we see with a high degree of confidence that we canexpect less snow in warmer climates. In scenarios where the world produces more greenhouse gas emissions, that'sworse for snow seasons.

Should states be worried about water supplies?

This winter's forecast isn't extreme at this point, so the impact on the year's water supplies is a pretty big question mark.

Snowpack – how much snow is on the ground in March or April –sums up the snowfall, minus the melt, for the year. The snowpack also affects water supplies for the rest of the year.

TheWest's water infrastructure systemwas built assuming there would be a natural reservoir of snow in the mountains. California relies on the snowpack forabout a thirdof its annual water supply.

However, rising temperatures are leading toearlier snowmelt in some areas. Evidence suggests that climate change is also expected to causemore rain-on-snow eventsat high elevations, which can cause very rapid snowmelt.

Both create challenges for water managers, who want to store as much snowmelt runoff as possible in reservoirs so it's available through the summer, when states need it most for agriculture and for generating hydropower to meet high electricity demand. If the snow melts early, water resource managers face some tough decisions, because they also need to leave room in their reservoirs to manage flooding. Earlier snowmelt sometimes means they have to release stored water.

When we look at reservoir levels in the Colorado River basin, particularly the big reservoirs – Lake Powell and Lake Mead – we see apattern of decline over time. They have had some very good snow and water years, and also particularly challenging ones, including along-running drought. The long-term trends suggest an imbalance between supply andgrowing demand.

What else does snowfall affect, such as fire risk?

During low-snow years, the snowpack disappears sooner, and thesoils dry out earlierin the year. That essentially leaves a longer summer dry period andmore stress on trees.

There is evidence that we tend to havebigger fire seasons after low-snow winters. That can be because the forests are left with drier fuels, which sets the ecosystem up to burn. That's obviously a major concern in the West.

Snow is also important to a lot of wildlife species that are adapted to it. Oneexample is the wolverine, an endangered species that requires deep snow for denning over the winter.

What snow lessons should people take away from climate projections?

Overall, climate projections suggest our biggest snow years will beless snowy in anticipated warmer climates, and thatvery low snow yearsare expected to be more common.

But it's important to remember that climate projections arebased on scenariosof how much greenhouse gas might be emitted in the future – they are not predictions of the future. The worldcan still reduce its emissionstocreate a less risky scenario. In fact, while the most ambitious emissions reductions are looking less likely, theworst emissions scenarios are also less likelyunder current policies.

Understanding how choices can change climate projections can be empowering.Projections are saying: Here's what we expect to happen if the world emits a lot of greenhouse gases, and here's what we expect to happen if we emit fewer greenhouse gases based on recent trends.

The choices we make will affect our future snow seasons and the wider climate.

This article has been updated to correct the references to Denver, which saw one of its latest snowfalls on record.

Adrienne Marshall, Assistant Professor of Geology and Geological Engineering, Colorado School of Mines

Ski season is here, but while the eastern half of the U.S.digs out from wintery storms, the western U.S. snow season has ...